Neural Horticulture: a look at recent work on pruning

Deep Neural networks (DNNs) can be big. For instance, VGG-16 (from the good old days of 2014) has 17 million parameters in one of its linear layers. It is desirable for DNNs to be smaller for severals reasons, not limited to: realtime applications, fitting in the memory of embedded devices, writing a conference paper on network compression.

A popular means of shrinking these networks is through pruning. However, pruning can mean many things (e.g. a removal of excess material from a tree or shrub). To prevent any further confusion, let’s define the pruning procedure in the following way:

- Train a big neural network

- Remove a subset of the connections according to some scheme

- Fine-tune the network (i.e. keep training it with a low learning rate) and save it somewhere

- Go back to step 2 until the network has no more connections and your script crashes

In this blog post, we’ll look at two recent papers that indicate that (i) it’s often preferable to train your pruned network or even a simple, smaller architecture from scratch, and (ii) pruning can be seen a form of architecture search. In a bizarre coincidence, one of the authors on the second paper shares my name.

Rethinking pruning

In “Rethinking the Value of Network Pruning”, the authors have shown that it is possible to entirely avoid terrible puns in paper titles. In addition to this, they have done some very interesting experiments.

For their pruning, the authors wisely avoid Step 4 above, presumably because they don’t want their scripts to crash. They train a big network, pick a desired compression rate, and then prune connections all at once to get their smaller network. This is then fine-tuned for several epochs. This is different to what we do (yes, the other paper was mine all along!). More on that later. They use Network Slimming, Sparse Structure Selection and Deep compression as their pruning schemes.

The authors compare these pruned networks to networks with the same architectures trained from scratch. These smaller networks are trained from scratch in two ways: Scratch-E, in which they train the small networks for the same number of epochs as the original big network, and Scratch-B where they train them for more epochs than the original: the motivation being that the smaller network is less expensive to train per epoch.

In most of their experiments, Scratch-E isn’t as good as the fine-tuned pruned models, but is pretty close in performance. Scratch-B frequently outperforms the fine-tuned models1. So, this implies that if you know what these small architectures look like, you can just train them from scratch rather than go through the rigmarole of pruning.

They also observe that the architectures obtained through pruning are fairly consistent; they prune 40% of the channels of a VGG net multiple times and get very similar structures (in terms of channel widths) each time. This leads the authors consider whether it is possible to obtain generalisable design principles2 by observing these pruned structures.

The one with the bad title

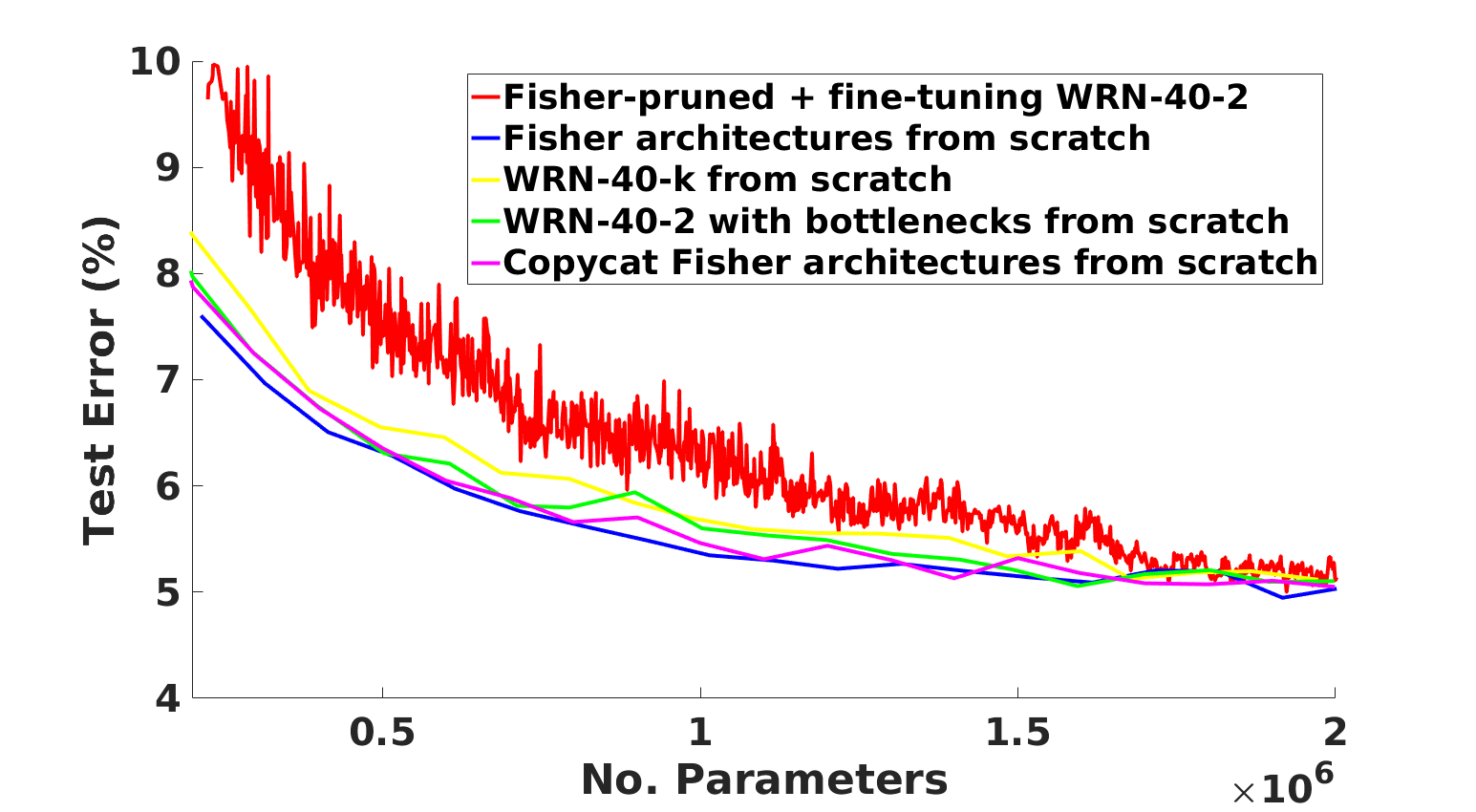

This leads us to the appallingly named “Pruning neural networks: is it time to nip it in the bud?”. We use Fisher pruning (https://arxiv.org/abs/1801.05787, https://arxiv.org/abs/1611.06440) on a WideResNet, and for Step 2 above we prune a single connection between rounds of fine-tuning (specifically, we remove a channel connection between a pair of convolutions from one of the network’s blocks). So, rather than having a single pruned network we have over 1000 of them. The first with 1 connection removed, then 2, then 3, then … I’ll stop now. Each of these pruned-and-tuned networks is a point on the red curve in the following yes-it-was-done-in-MATLAB plot:

Of course this isn’t the only way to get a family of networks. You could take the original WideResNet and change the channel width multiplier, or you could introduce a bottleneck into each of its residual blocks, similar to what we did in https://arxiv.org/abs/1711.026133. In fact, if you do this, and train the resulting networks from scratch you get the yellow and green curves above. Notice that these networks are almost always better than our pruned ones! You can shrink your original network in a very simple, uniform manner and train it from scratch rather than going through the procedure above that would have crashed your machine anyway!

That’s not the end of the story however. As in the first paper, we take our pruned architectures and see what happens if we train them from scratch. It turns out they are not only better than their pruned-and-tuned counterparts, but they are largely better than our simple small networks. Pruning appears to be giving us good architectures, that just need to be trained from scratch to reveal their inner beauty.

So, what happens if we take one of our pruned architectures and just linearly scale its brand new structure for different parameter totals? We get the pink curve above. A new family of architectures that performs well based on a single pruned network. Not bad.

In conclusion, it’s good to rethink the value of whether to nip pruning in the bud. The evidence suggests (i) if you’re lazy, just train a small network instead, (ii) if you’re a bit less lazy, prune a big network and then train the resulting network from scratch. Of course we haven’t touched upon the benefits of pruning for transfer learning, and there may well be networks/tasks/trees that do benefit from pruning for performance. I hope this at least got you thinking. About gardening.

1 If the small network needed more epochs to train, then it seems likely the big network needed more epochs too. This may have led to better pruned architectures.

2 A good design principle is to not use a VGG net as it’s really, really too big.

3 We didn’t come up with bottlenecks. This is a gratuitous self-citation.