Knowledge Distillation with Hardware Constrained Students

It would be pretty hard to deploy an ensemble of 115-million-parameter SENets on a smart watch. Although the 2017 ImageNet winner was pretty good at distinguishing between dog breeds, it’s a little less good at mobile cache performance.

Ignoring the hyperbole, this is a problem that we are facing increasingly often in the post-Moore’s law era. Luckily for us, network designers and computer architects have gotten pretty creative, and there are now lots of techniques for ditching large portions of modern networks and fitting to very small parameter budgets (Denil et al., 2013; Han et al., 2015; Theis et al., 2018); this is something that we’re going to have to exploit properly if we ever want our smart watches to distinguish our huskies from our neighbour’s malamutes.

The problem arises when computer architects write off neural networks as ‘just matrix multiplication’, and network architects write off computers as abstract things that exist somewhere and do FLOPs, or something.

The result, rather than being complementary acceleration techniques, usually ends up with the network pruning a layer down, the compiler padding the layer back up, and everyone taking home the wrong dog.

In this post we’ll talk a little bit about a new method for reshaping networks to perform well on specific platforms using empirical observations of hardware behaviour.

Channel pruning and layer fusion, name a more iconic duo

The need to address the symptoms of these bifurcated communities is best shown with a case study.

Many “inference acceleration frameworks” use graph optimisations to streamline the execution of inference on some target hardware. One such graph optimisation is layer fusion, whereby kernels with similar input and output dimensions are vertically fused so that they can be used in a single call. If two layers are similar enough in size, one of the two will often be padded to allow for layer fusion.

Now take, for example, an Inception module from GoogLeNet, which has many fusable 1x1 convolution layers. Many of these 1x1 filters can be pruned, but, performing this pruning means that the graph optimiser can’t perform layer fusion unless it pads back the filters that have been pruned.

In this case, both sides of the stack are losing out. The model is moderately less accurate, because some filters have been pruned, and the compiler is slightly less happy, because it’s not getting the same throughput.

Hopefully you can see now that just optimising for FLOPs is not enough, and that compression techniques should probably take some real hardware performance into account.

HAKD: Hardware Aware Knowledge Distillation

The neural architecture search space is already very large, and adding in the hardware optimisation space makes it even more unmanageable, so we need to find some heuristic to guide us.

One lazy way to do this is to apply a pruning scheme to some pretrained network and then, by polling the target hardware, we can explore the neighbours of the point we settled on and see if there are any more optimal spaces from the perspective of inference time.

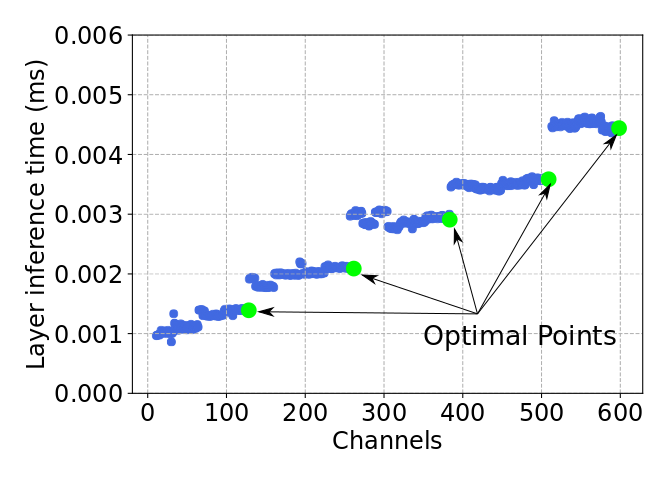

Exhaustively searching this space for a small number of layers gives us some interesting results:

In this example, we take a layer of a large ResNet and iteratively prune away one filter at a time, benchmarking the inference speed at each step. What forms, rather than a linear speedup, is a staircase with clearly optimal points.

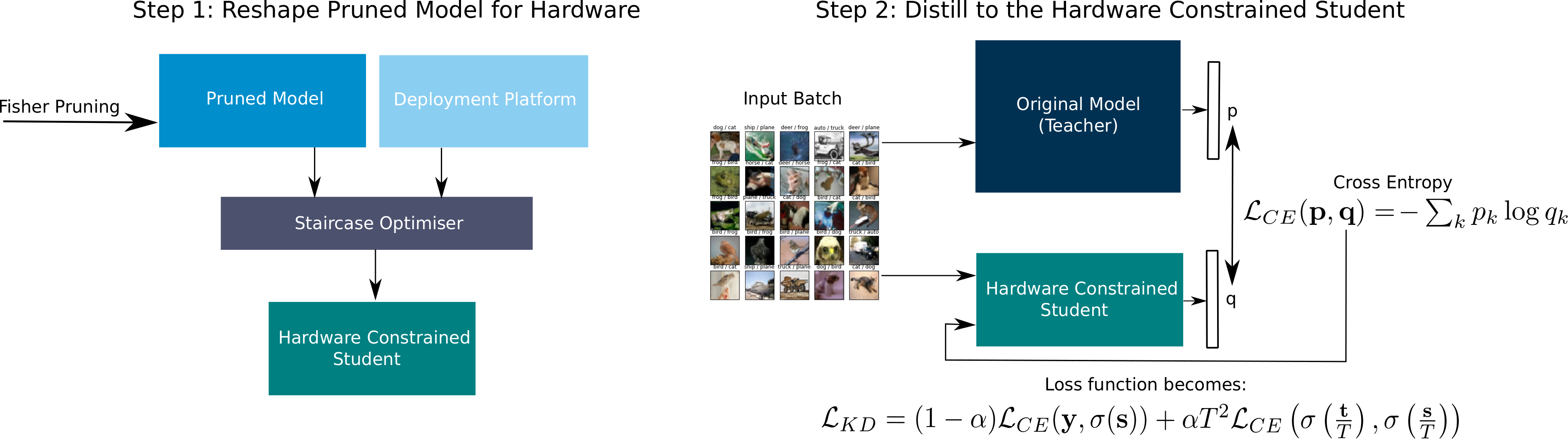

We propose a two step process, whereby we:

- Apply a pruning technique, and watch it settle on a step of the staircase

- Reset the layer width chosen by the pruning technique to be the optimal point on that staircase.

Then, to train our new network shape, we propose the use of knowledge distillation from the original model. In this sense, our pipeline looks like this:

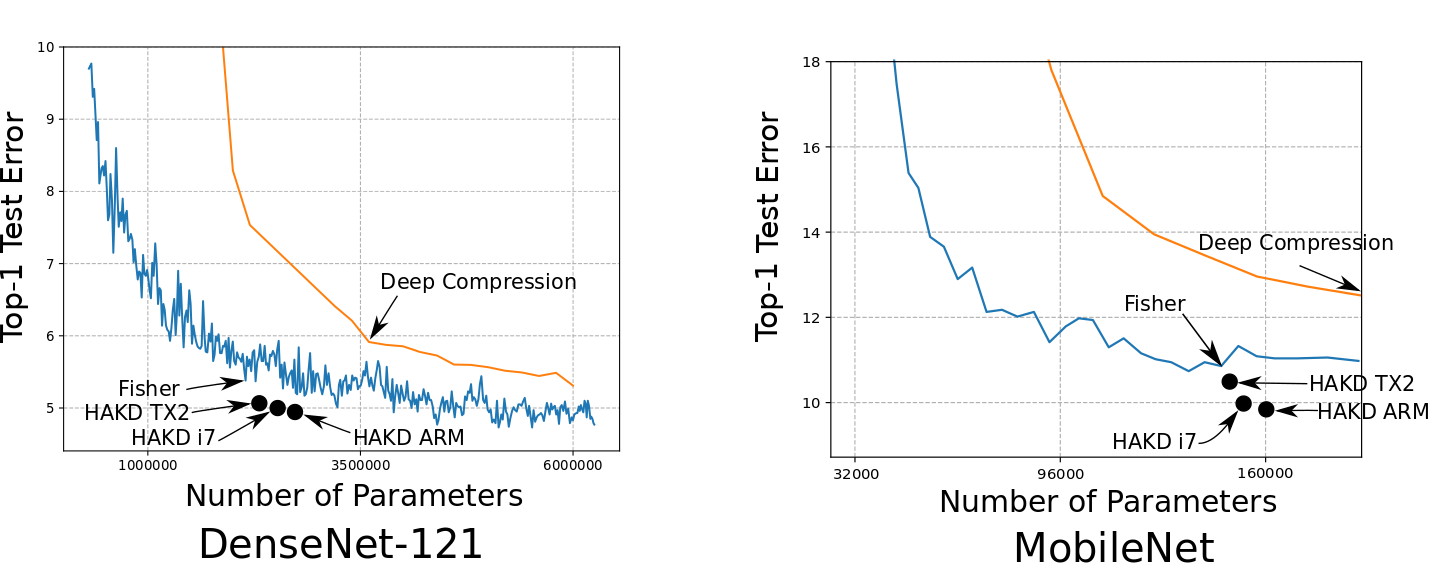

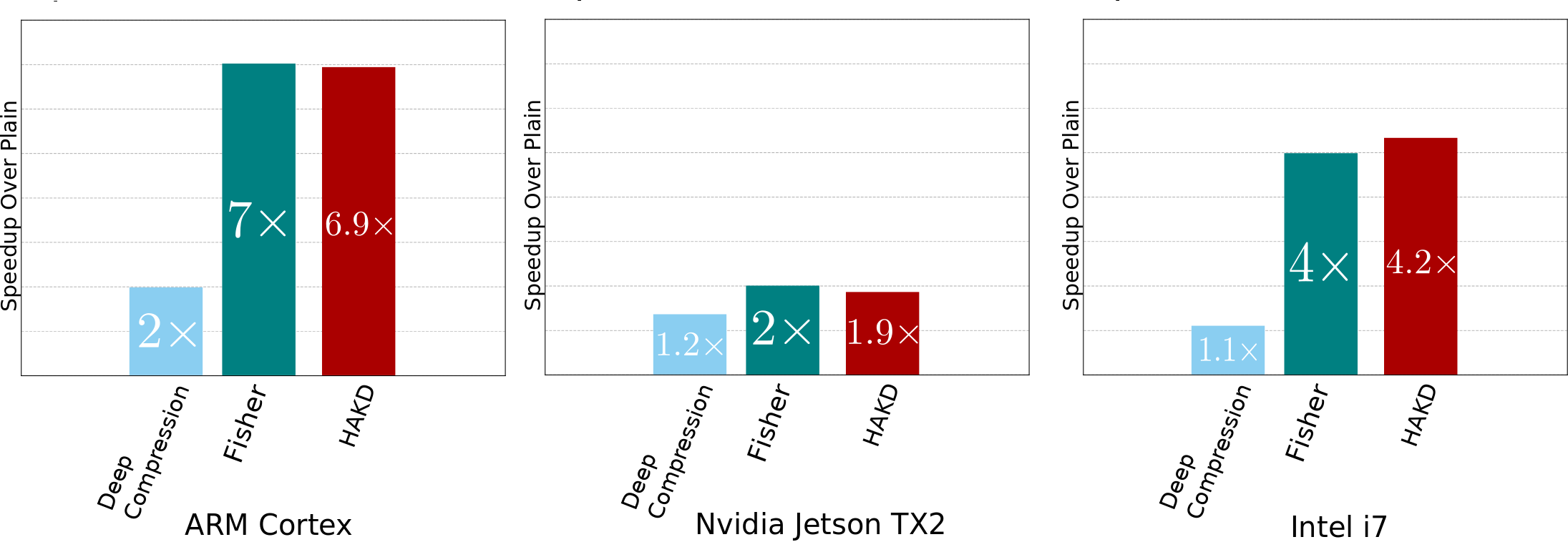

We tried this out on DenseNet-121 and MobileNet, using the CIFAR-10 dataset and a few different devices (an i7 CPU, TX2 GPU, and an ARM Cortex CPU). The result is rather pleasing:

The compression technique we chose to guide our search was Fisher pruning (we also compare against Deep Compression, because that has >1200 citations) and we are able to adjust the points to more accurate points in the space for the same inference time:

By moving each layer to an optimal point on its staircase, we are able to moderately increase the available number of parameters without affecting the total inference time. This way, we can sleep safe at night in the knowledge that our neural networks are making the most of the hardware they are constrained to.

For more details, see the full paper.